7 Tips to Make the Most of Online Therapy During the COVID-19 Outbreak

A couple of years ago — long before COVID-19 was an unfortunate glimmer in the CDC’s eye — I made the decision to switch from in-person therapy to telemedicine.

As someone who has historically struggled with opening up to therapists, my hope was that I would find it easier to be vulnerable if I could hide behind a screen. What I found was that I was able to disclose more, and as a result, it deepened the therapeutic relationship.

Not only did this transform my therapy experience — it also unwittingly prepared me for the huge shift to telehealth that’s now happening in light of the recent COVID-19 outbreak.

If you’re looking to start online therapy, or if your therapist has moved their practice to digital for the unforeseeable future, it can be a jarring transition.

While it can be a big adjustment, online therapy can be an amazing and worthwhile support system — particularly in a time of crisis.

So how do you make the most of it? Consider these 7 tips as you make your transition to teletherapy.

1. Carve out a safe space and intentional time for therapy

One of the most touted benefits of online therapy is the fact that you can do it any time, anywhere. That said, I don’t necessarily recommend that approach if you can avoid it.

For one, distractions are never ideal when you’re trying to work — and therapy is rigorous, difficult work sometimes!

The emotional nature of therapy makes it even more important to have some space and time set aside to engage with this process fully.

If you’re self-isolating with another person, you could also ask them to wear headphones or take a walk outside while you do therapy. You might also get creative and create a blanket fort with string lights for a more soothing, contained environment.

No matter what you decide, make sure you’re prioritizing therapy and doing it in an environment that feels safest for you.

2. Expect some awkwardness at first

No matter what platform your therapist is using and how tech-savvy they are, it’s still going to be a different experience from in-person — so don’t be alarmed if it doesn’t feel like you and your therapist are “in-sync” right away.

For example, when my therapist and I used messaging as our primary mode of communication, it took some time for me to get used to not being replied to right away.

It can be tempting to think that some discomfort or awkwardness is a sign that online therapy isn’t working for you, but if you can keep an open line of communication with your therapist, you might be surprised by your ability to adapt!

It’s also normal to “grieve” the loss of in-person support, especially if you and your therapist have worked together offline before.

It’s understandable that there could be frustration, fear, and sadness from the loss of this type of connection. These are all things that you can mention to your therapist as well.

3. Be flexible with the format of your therapy

Some therapy platforms use a combination of messaging, audio, and video, while others are a typical session over webcam. If you have options, it’s worth exploring what combination of text, audio, and video works best for you.

For example, if you’re self-isolated with your family, you may rely on messaging more frequently as not to be overheard by someone and have as much time as you need to write it. Or if you’re burnt out from working remotely and staring at a screen, recording an audio message may feel better for you.

One of the benefits of teletherapy is that you have a lot of different tools at your disposal. Be open to experimenting!

4. Lean into the unique parts of telemedicine

There are some things you can do with online therapy that you can’t necessarily do in-person.

For example, I can’t bring my cats to an in-person therapy session — but it’s been special to introduce my therapist to my furry companions over webcam.

Because online therapy is accessible in a different way, there are unique things you can do to integrate it into your daily life.

I like to send my therapist articles that have resonated with me for us to talk about later, set up small daily check-ins instead of just once weekly, and I’ve shared written gratitude lists over text during especially stressful times.

Getting creative with how you use the tools available to you can make online therapy feel a lot more engaging.

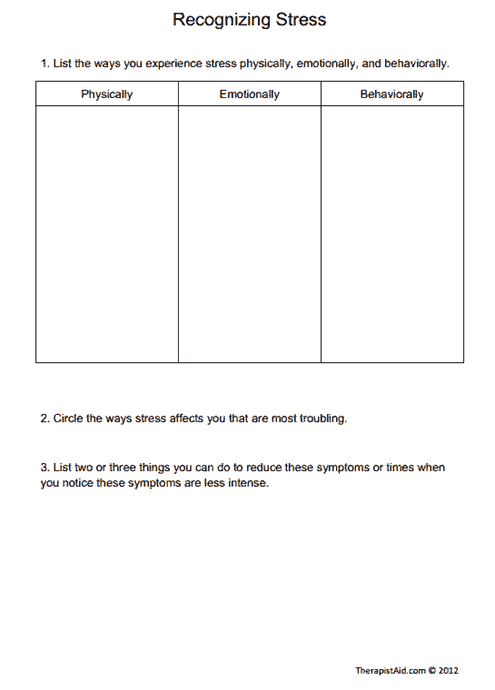

5. In the absence of bodily cues, practice naming your emotions more explicitly

If you’ve been in in-person therapy for a while, you may be used to your therapist observing your bodily cues and facial expressions, and sort of “intuiting” your emotional state.

Our therapists’ ability to read us is something we might take for granted as we pivot to telemedicine.

This is why it can be really beneficial to practice naming our emotions and reactions more explicitly.

For instance, if your therapist says something that strikes a nerve, it can be powerful to pause and say, “When you shared that with me, I found myself feeling frustrated.”

Similarly, learning to be more descriptive around our emotions can give our therapists useful information in the work that we do.

Rather than saying “I’m tired,” we might say “I’m drained/burnt out.” Instead of saying “I’m feeling down,” we might say, “I’m feeling a mix of anxiety and helplessness.”

These are useful skills in self-awareness regardless, but online therapy is a great excuse to start flexing those muscles in a safe environment.

6. Be willing to name what you need — even if it seems ‘silly’

With COVID-19 in particular, an active pandemic means that many of us — if not all — are struggling with getting some of our most fundamental human needs met.

Whether that’s remembering to eat and drink water consistently, grappling with loneliness, or being fearful for yourself or loved ones, this is a difficult time to be a “grownup.”

Taking care of ourselves is going to be a challenge at times.

It can be tempting to invalidate our responses to COVID-19 as being an “overreaction,” which can make us reluctant to disclose or ask for help.

However, your therapist is working with clients every day who undoubtedly share your feelings and struggles. You aren’t alone.

What should I say?

Some things that might be helpful to bring to your therapist during this time:

- Can we brainstorm some ways to help me stay connected to other people?

- I keep forgetting to eat. Can I send a message at the beginning of the day with my meal plan for the day?

- I think I just had my first panic attack. Could you share some resources for how to cope?

- I can’t stop thinking about the coronavirus. What can I do to redirect my thoughts?

- Do you think my anxiety around this makes sense, or does it feel disproportionate?

- The person I’m quarantined with is impacting my mental health. How can I stay safe?

Remember that there’s no issue too big or too small to bring to your therapist. Anything that’s impacting you is worth talking about, even if it might seem trivial to someone else.

7. Don’t be afraid to give your therapist feedback

A lot of therapists who are making the shift to telemedicine are relatively new to it, which means there will almost certainly be hiccups along the way.

Online therapy itself is a more recent development in the field, and not all clinicians have proper training on how to translate their in-person work to a digital platform.

I don’t say this to undermine your faith in them — but rather, to remind and encourage you to be your own best advocate in this process.

So if a platform is cumbersome to use? Let them know! If you’re finding that their written messages aren’t helpful or that they feel too generic? Tell them that, too.

As you both experiment with online therapy, feedback is essential to figuring out what does and doesn’t work for you.

So if you can, keep communication open and transparent. You might even set aside dedicated time each session to discuss the transition, and what has and hasn’t felt supportive for you.

Online therapy can be a powerful tool for your mental health, especially during such an isolating, stressful time.

Don’t be afraid to try something different, vocalize what you need and expect, and be willing to meet your therapist halfway as you do this work together.

Now more than ever, we need to protect our mental health. And for me? I’ve found no greater ally in that work than my online therapist.

Source