I was sitting alone in the hallway of the Carter Center conference area in Atlanta during the 2012 Rosalynn Carter Symposium on Mental Health Policy. I had just finished being a panelist and talking about how employment and education helped me overcome the stigma associated with my depression. The conference was still in session, so I had the hallway to myself. I sat quietly, reflecting on the fact that I had been invited to speak here as both a clinician working in community mental health and a person living with depression.

Two scenes flashed through my mind highlighting two very different points in my life: getting offered a job as a therapist at the mental health center where I completed my internship for my Master’s in social work, and sitting in a psych ward on the eve of my 18thbirthday, wondering if I would graduate from high school.

Persevering Through Depression

It took many years of perseverance for me to become that professional sitting on a panel at a national conference. Though I managed to graduate from high school, I dropped out of college at 19 as my depression worsened. I was unemployed, and my only income was Social Security disability. Years of failed depression treatments included medication and talk therapy.

I spent most of my time alone doing what I refer to as “stewing in my own depressive juices.” This lasted for 10 years. During that time, I was challenged by the symptoms of mental illness— insomnia, loss of appetite, lack of concentration, suicidal thoughts. After a decade of being unemployed and living on Social Security, I decided that for my own survival, I had to return to school and complete my social work degree. Of course, my depression was against this:

“You can’t go back to school; you will fail.”

“You won’t be able to concentrate enough to complete your assignments.”

“You’re too stupid to get a college degree.”

Somehow, I decided to talk back to these negative thoughts. My response was simple: “I’m just going to do the best I can.”

And I did. I got myself back to school and finished my degree in social work. Around that time, I also tried a different treatment for my depression, and it worked. Things got easier.

Today, I feel incredibly lucky to say that I am doing exactly what I want to be doing. But really, luck had little to do with it. Besides my symptoms of depression, I faced an additional barrier to school, employment and inclusion in general: unhelpful attitudes from well intentionedhealth professionals—in other words, stigma.

Learning To Reject Stigma

One mental health professional once told me, “Maybe you’re not getting better because you’re not trying hard enough.” Another warned me, “You might not be ready to go back to school full time. Shouldn’t you just take one class and see how that goes?” A psychiatrist decided, without asking for my opinion, that I should be sent to live in a group home for people with mental illness. (That did not happen, and that treatment relationship ended that day.)

These scenarios were fueled by the stigma associated with mental illness—stigma that ultimately serves to limit and exclude rather than encourage and include. Had I listened to those professionals, I might never have returned to school or entered the workforce.

So how did I overcome the stigma that I faced? I rejected it. Rejecting—or overcoming—stigma, whether it be self-stigma, public stigma or structural stigma, is one of the keys for those of us living with mental illness. This is not an easy task, to be sure, but it is becoming more possible and a bit easier as more and more of us of speak out about our mental health conditions.

After working as a therapist and witnessing the negative effects of stigma on clients and their family members, I decided to develop a stigma-reduction training curriculum called “Overcoming Stigma.” I spent several months reading every scientific article I could find about stigma research. Most of it simply documented that stigma exists (in hospitals, in psychiatry, in substanceusetreatment centers, in pharmacies, universities, employment, housing, etc.) and that levels of stigma have not changed over the last decade.

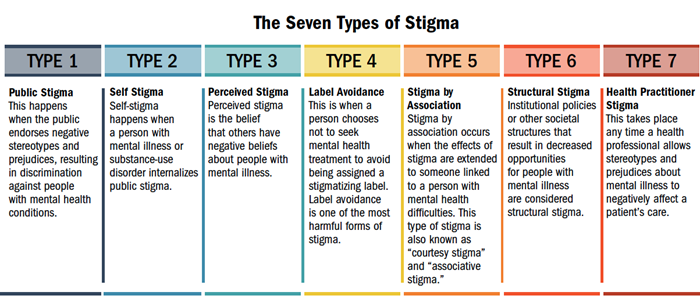

According to many studies, effectively reducing stigma pointed to one intervention: contact with someone successfully managing a mental illness. One shining example of this is NAMI’s In Our Own Voice (IOOV) program. People with mental health conditions share their powerful personal stories in this free 60- or 90-minute presentation. I decided to integrate elements of IOOV into the beginning of my trainings by briefly disclosing my own depression and giving a few examples of my experiences with stigma. The rest of the training includes a description of the seven most common types of stigma experienced by people with mental illness and substance-use disorders, research about the effects of these stigmas, ways to reduce stigma, and the clinical and agency assessment tools I developed.

I have presented Overcoming Stigma trainings in many different health care settings, and the curriculum continues to evolve, always guided by the latest stigma research. Recent research shows that stigma training needs to be ongoing instead of a one-time thing and, it likely needs to address many stigmas all at once.

My trainings get everyone involved in the discussion; I like to ask for anecdotes from attendees. Here are some real-life examples of stigma shared by health care professionals who have attended my trainings over the past several years:

• A cardiac surgeon said he would not do surgery on a person with schizophrenia because he didn’t think the person would be able to do the required follow-up care.

• A therapist shared that as a Ph.D. student, he was told he would lose his scholarship if he left for “depression” treatment but could keep it if he left for “medical” treatment.

• A mother puts off making an appointment for her daughter to see a therapist despite her daughter experiencing severe symptoms of anxiety because she doesn’t want her daughter to be labeled as “crazy.”

• A physician attendee said it was well known in her neighborhood that her son had been hospitalized with bipolar disorder and no one acknowledged this fact (much less offered any type of support).

• A mental health clinician working in an emergency room said doctors and nurses often referred to patients in the ER with mental illness as “her patients,” rather than “our patients.”

If I do my job well, attendees leave with the understanding that we all have a role to play in reducing these harmful kinds of stigma. Personally, I still experience stigma, but I am no longer limited by it. I sometimes even chuckle when I hear someone say something particularly stigmatizing because I immediately think, “Well, that’s going to be part of my next training.” That’s not to say it isn’t still discouraging to see or hear things that continue to perpetuate stigma, but for me, there is a feeling of freedom and power in being able to turn a potential lost opportunity into one that is gained.

Gretchen Grappone, LICSW is a trainer and consultant with Atlas Research in Washington, D.C. Her work includes projects with VA medical centers, community mental health centers and other health care settings around the country. She lives in New York City.

https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/October-2018/Overcoming-Stigma