It is very normal for all children to have specific fears at some point in their childhood. Even the bravest of hearts beat right up against their edges sometimes. As your child learns more about the world, some things will become more confusing and frightening. This is nothing at all to worry about and these fears will usually disappear on their own as your child grows and expands his or her experience.

In the meantime, as the parent who is often called on to ease the worried mind of your small person, it can be helpful to know that most children at certain ages will become scared of particular things.

When is fear or anxiety a problem?

Fear is a very normal part of growing up. It is a sign that your child is starting to understand the world and the way it works, and that they are trying to make sense of what it means for them. With time and experience, they will come to figure out for themselves that the things that seem scary aren’t so scary after all. Over time, they will also realise that they have an incredible capacity to cope.

Fears can certainly cause a lot of cause distress, not only for the kids and teens who have the fears, but also for the people who care about them. It’s important to remember that fears at certain ages are completely appropriate and in no way are a sign of abnormality.

The truth is, there really is no such thing as an abnormal fear, but some kids and teens will have fears that are more intense and intrusive. Even fears that seem quite odd at first, will make sense in some way.

For example, a child who does not want to be separated from you is likely to be thinking the same thing we all think about the people we love – what if something happens to you while you are away from them? A child who is scared of balloons would have probably experienced that jarring, terrifying panic that comes with the boom. It’s an awful feeling. Although we know it passes within moments, for a child who is still getting used to the world, the threat of that panicked feeling can be overwhelming. It can be enough to teach them that balloons pretend to be fun, but they’ll turn fierce without warning and the first thing you’ll know is the boom. #not-fun-you-guys

Worry becomes a problem when it causes a problem. If it’s a problem for your child or teen, then it’s a problem. When the fear seems to direct most of your child’s behaviour or the day to day life of the family (sleep, family outings, routines, going to school, friendships), it’s likely the fear has become too pushy and it’s time to pull things back.

So how do we get rid of the fear?

If you have a child with anxiety, they may be more prone to developing certain fears. Again, this is nothing at all to worry about. Kids with anxiety will mostly likely always be sensitive kids with beautiful deep minds and big open hearts. They will think and feel deeply, which is a wonderful thing to have. We don’t want to change that. What we want to do is stop their deep-thinking minds and their open hearts from holding them back.

The idea then, isn’t to get rid of all fears completely, but to make them manageable. As the adult in their lives who loves them, you are in a perfect position to help them to gently interact with whatever they are scared of. Eventually, this familiarity will take the steam out of the fear.

First of all though, it can be helpful for you and your child to know that other children just like them are going through exactly the same experience.

An age by age guide to fears.

When you are looking through the list, look around your child’s age group as well. Humans are beautifully complicated beings and human nature doesn’t tend to stay inside the lines. The list is a guide to common fears during childhood and the general age at which they might appear. There are no rules though and they might appear earlier or later.

Infants and toddlers (0-2)

• Loud noises and anything that might overload their senses (storms, the vacuum cleaner, blender, hair dryer, balloons bursting, sirens, the bath draining, abrupt movement, being put down too quickly).

Here’s why: When babies are born, their nervous systems are the baby versions. When there is too much information coming to them through their senses, such as a loud noise or being put down too quickly (which might make them feel like they’re falling), it’s too much for their nervous systems to handle.

• Being separated from you.

Here’s why: At around 8-10 months, babies become aware that when things disappear, those things still exist. Before this, it tends to be ‘out of sight, out of mind’. From around 8 months, they will start to realize that when you leave the room you are somewhere, just not somewhere they can see you. This may be the start of them being scared of being separated from you, as they grapple with where you’ve gone, and when you’ll be coming back. During their second year, they begin to understand how much they rely on your love and protection. For a while, their worlds will start and end with you. (Though for you in relation to your little heart stealers, it will probably always be that way.)

• Strangers.

Here’s why: An awareness of strangers will peak at around 6-8 months. This is a good thing because it means they are starting to recognize the difference between familiar and unfamiliar faces. By this age, babies will have formed a close connection with the ones who take care of them. They will know the difference between you and the rest of the world, not only because of what you look like or the sound of your voice, but also because of what you mean for them. For many babies, strangers and ‘sort of strangers’ – actually anyone outside of their chosen few – will need to move gently. Babies will be sensitive to their personal space and will be easily scared by anyone who quickly and unexpectedly enters that space.

(At this age, separation anxiety and stranger anxiety can be a tough duo for any parent. Your little person doesn’t like being away from you, but they might not be too fond of the person you leave them in the care of. It can be tough, but hang in there – it will end.)

• People in costume.

Soooo lemme get this right – you’re putting me in front of a big man in a red suit with a white beard the likes I’ve never seen before and you want me to sit on his lap? Nope. Not today. Probably not until I’m like, five. Or 72. Or when I figure that out he brings stuff. Then I might get close enough to tell him want I want, or maybe I’ll throw him a letter or something. And I don’t get the point of the big people-sized rabbits that carry baskets of shiny wrapped thin- … actually, wait. No to the rabbit people. Yes to the shiny wrapped things. Just put them where I can reach them and leave. K?

• Anything outside of their control (exuberant dogs, a flushing toilet, thunder).

Here’s why: At around age one when your child starts to take little steps, he or she will start to experiment with their independence. This might look like moving small distances away from you or wanting to play with their food or feed themselves. With this, comes an increasing need for them to have a sense of predictability and control over their environment. Anything that feels outside of their control might seem frightening.

Preschoolers (3-4)

• Lightning, loud noises (the bath draining, thunder, balloons bursting, fireworks, loud barking dogs, trains) and anything else that doesn’t make sense.

Here’s why: They will become very aware of their lack of control in the world. Because of this, they might show a fear of things that seem perfectly innocent to the rest of us to make no sense at all to a grown up. It can be a scary world when you’re new to the job of finding your way in it!

• Anything that isn’t as it usually is – (an uncle who shows up with a new beard, a grandparent with different colored hair).

Here’s why: It’s hard enough when strangers are strangers, but when favorite people look like strangers … whoa! Familiarity is the stuff of happy days. There’s so much in the world to get used to when you’re fairly new to the job. When things change unexpectedly, it can feel like being back at the beginning and having to get comfortable all over again. Massive ‘ugh’.

• Scary noises, Halloween costumes, ghosts, witches, monsters living under the bed, burglars breaking into the house, burglars making friends with the monsters living under the bed and ganging up – and anything else that feeds their hardworking imaginations.

Here’s why: Their imaginative play is flourishing and their imaginations are wonderfully rich. At this age, they will have trouble telling the difference between fantasy and reality.

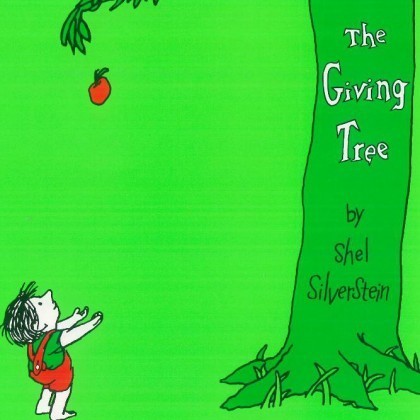

• The things they see on television or read in books might fuel their already vivid imaginations and come out as scary dreams. This might bring on a fear of the dark or being alone at night.

Here’s why: At this age, kids can struggle a little to separate fantasy from reality. If they hear a story about a pirate for example, as soon as the lights are out they might imagine Captain-Russell-With-The-Boat-Who-Steals-Toys-From-Sleeping-Kids is waiting under their bed, ready to cause trouble. A calming bedtime routine and happy, pirate-free stories can help to bring on happy zzz’s.

• People in costume (Santa, the Easter Bunny, story or cartoon characters.)

Here’s why: At this age, grown-ups in dress-ups are no more adorable than they were in the baby days. If Santa doesn’t know what they want, he might just have to work harder, because there’s no way they’ll be telling him in person. Lucky he’s magic and has people on the ground who know the important stuff.

• Being separated from you or being away from the people or pets they love.

Here’s why: They might worry that something will happen to themselves, the people they love or a pet, particularly if something happens to someone close to them.

• The dark and being on their own at night, particularly if they hear a strange sound or see lights or shadows on the wall.

Here’s why: The dark can feel scary at this age. With their imaginations running wild and free, they might put their own explanations to strange night-time noises or shadows on the wall. They might convince themselves that the sound of a moth hitting a light bulb is definitely a robber, because no other explanation makes any sense.

5-6 years.

• Being separated from you.

Here’s why: At this age, children might show a strong reaction to being separated from one or either or their parents. This comes as they start to see outside of themselves and realize that bad things can happen to the people they love. They might want to avoid school or sleepovers so they can be with you and know that you’re safe and sound.

• Ghosts, monsters and witches – and anything else that bumps around in their wonderfully vivid imaginations. This can also show itself as a fear of the dark – because we all know the spooky things love it there.

Here’s why: Their imaginations are still hard at work so anything they can bring to life in there will be fuel for fear.

• The dark, noises, being on their own at night, getting lost, getting sick.

Here’s why: As well as being scared of things that take up precious real estate in their heads, they might also become scared of things could actually happen. These are the sorts of things that might unsettle all of us from time to time.

• Nightmares and bad dreams.

Here’s why: Because of the blurred line between fantasy and reality, bad dreams can feel very real and are likely to peak at this age.

• Fire, wind, thunder, lightning – anything that seems to come from nowhere.

Here’s why: They are still trying to grasp cause and effect and their minds are curious and powerful. They might scare themselves trying to explain where scary things come from. Lightning might mean the sky is about to catch fire. Thunder – who knows – but anything that loud surely doesn’t come in ‘cute’ or ‘chocolate coated’.

7-11 years.

• Monsters, witches, ghosts, shadows on the wall at night.

Here’s why: Though their thinking is more concrete, children at this age will still have a very vivid imagination.

• Being at home alone.

Here’s why: They’re still learning to trust the world and their capacity to cope with small periods of time on their own, without you. Staying at home alone might be exciting, scary or both – then there’s that imagination of theirs that might still ambush them at times.

• Something happening to themselves or the people (or pets) they care about.

Here’s why: They start to understand that death affects everyone at some point and that it’s permanent. They might start to worry about something happening to themselves or the people (or pets) they care about.

• Being rejected, not liked, or judged badly by their peers (buckle up – this one might stay a while).

Here’s why: This can show up at any age but it might ramp up or towards the end of these years. This is because they will start to have an increased dependence on their friendships as they gear up for adolescence.

Adolescents (12+)

• What their peers are thinking of them.

One of the primary developmental goals of adolescence is figuring out how they are and where they fit into the world. As they do this, they will start to worry about what other people think. They also have the job of moving towards independence from you. What their friends think will take on a new importance as they start to make the move away from their family tribe and towards their peer one. They will always love you (though it might not feel that way if you’re weathering one of the storms that comes with adolescence!), but their dependency on you will shift. This is healthy and important and the way it’s meant to be. It’s all part of them growing from small, dependent humans into capable, independent, thriving bigger ones.

• Themselves or someone they care about getting hurt, becoming sick or dying.

Here’s why: They will be very aware that accidents happen, people get sick, and sometimes you just can’t see it coming. This fear will probably have more muscle if they hear of someone around them becoming sick or getting hurt. Realising that people can break isn’t all bad for them. During adolescence, they will be particularly prone to taking silly risks. It’s all part of them extending into the world and learning what they are capable of. What’s important is keeping their fear at a level that it doesn’t get in the way of them being brave, learning new things, and finding safe ways to discover what they’re capable of.

• how they’re doing at school, exams, failure, getting into college or university, not being able to ‘make it’ after school.

Here’s why: They’re thinking about life after high school . They want to do well, live a good life, and chase the dreams they’ve been dreaming.

• Strangers getting into their room at night, war, terrorism, being kidnapped, natural disasters – and any other frightening thing they might hear about in the news.

Here’s why: They realize that bad things happen sometimes but don’t understand the likelihood and the rarity of such events. With their increasing time on social media, they will tend to hear about bad news more often and come to believe that the risk of it happening to them is greater than it actually is.

• Talking to you about important personal issues.

Here’s why: It’s their job during adolescence to learn how to need you less. Adolescence isn’t always gentle with it’s developmental tasks and needing you less might be felt as ‘loving you less’. It’s not this – they love you as much as ever and however they might act towards you, what you think really does matter to them. They want you to be proud of them and they don’t want to disappoint you.

• Fear of missing out.

Here’s why: Being connected to their friends and being a part of what’s going on in their friendship group can feel like a matter of life or death. It sounds dramatic and for them, it is – but there is a good reason for this. For all mammals throughout history (think cave-people) and in nature, exclusion from the tribe means has meant almost certain death. For our adolescents, that’s how it feels when they feel on their outside of their tribe – it feels like death. In time they will learn that they will still feel connected to their friends even if they aren’t a part of everything that happens.

What to do:

For babies.

• Play peek-a-boo.

It will start to teach your baby that even when your face disappears, you’re still there. (That, and because the way their face lights up when they see you is gorgeous.)

• Teach them that separation is temporary, but go gently.

Practice leaving the room for short periods at a time so your baby can learn that you will always come back. Start with a minute, then, when your baby is ready, move up from there. When you are ready to leave them in the care of others, start with people they are familiar with for short periods, then work gently up from there.

• Always say goodbye.

Saying goodbye is the most important thing to do when you leave them. Making a quick dash while they are distracted might make things easier in the short term, but it will risk your baby being shocked to find you’re not there. This can add to their fears that you’ll disappear unexpectedly and it also runs the risk of chipping away at their trust. Have your ‘kiss and fly’ routine ready – tell them you’re leaving, a quick kiss, and let them know you’ll be back soon – or whatever works for you. It will be worth it in the long run.

For kids and adolescents.

• Give them plenty of information.

Even though kids at this age are aware of their environment, they don’t understand all of the things that go on in it. Thunder feels really scary – it’s unpredictable, it’s loud, and for a curious, powerful, inquisitive mind, it can surely feel as though the sky is breaking. For the child who is still getting used the world, it’s not so obvious that they won’t be sucked down the plughole when the bath drains. Point out what they can’t see. (‘Water fits down the plughole, but my arm won’t fit, neither will this boat, or the vacuum cleaner, or the car, or a hippo, or my foot, or my elbow. An ant would fit – wait – maybe that’s why ants don’t have baths! If I’m away from the plughole, nothing happens to me. See?’)

Give them all the information they need to put their scary things in context, where they belong. There’s no such thing as too much talk and at this age, they’re so hungry to learn. Make the most of it. By the time they reach adolescence, you will no longer be as smart (or sought after) as you think you should be. Celebrate their curiosity and feed it. They love hearing the detail of everything you know. You’re their hero and if anyone knows how to make sense of things, it’s you.

• Meet them where they are.

Some kids will love new things and will want to try everything and speak to everyone. Others will take longer to warm up. Unless it is a child who races towards the unknown like it’s the only thing to do, introduce new things and people gradually. There’s so much to learn and little people do a brilliant job of taking it all in when they’re given the space to do it at their own pace.

• Play

Play is such an important part of learning about the world. So much of their play is actually a rehearsal for real life. If your child is scared of something, introduce it during play. That way, they can be in charge of whatever it is they are worried about, whether it’s playing with the (unplugged) vacuum cleaner, being the monster, or having a ‘monster’ as a special pet. Give them some ideas, but let them take it from there. Through play they can practice their responses, different scenarios, and get comfortable with scary things from a safe distance.

• Be careful not to overreact.

It’s important to validate what your child is feeling, but it’s also important not to overreact to the fear. If you scoop your child up every time they become scared, you might be inadvertently reinforcing the fear. Rather than over-comforting, get down on their level and talk to them about it after naming what you see – ‘That balloon scared you when it popped didn’t it.’

• Don’t avoid.

It’s completely understandable that a loving parent would want to protect their child from the bad feelings that come with fear. Sometimes it feels as though the only way to do this is to support their avoidance of whatever it is that’s frightening. Here’s the rub. It makes things better in the short term, but in the long term will keep the fear well fed. The more something is avoided, the more that avoidance is confirmed as the only way to feel safe. It also takes away the opportunity for your child to learn that they are resilient, strong and resourceful enough to cope. It’s important for kids to learn that a little bit of discomfort is okay and that it’s a sign that they are about to do something really brave – and that they have what they need inside them to cope.

• Let them explore their fear safely.

Introduce the fear gently, in a way that your child can feel as though they have control. If your child is terrified of the vacuum cleaner, explore it with them while it isn’t plugged in. If your child is terrified of dogs, introduce them to dogs in books, in a movie, through a pet shop window, behind a fence. Do this gradually and in small steps, starting with the least scariest (maybe a picture of a dog) and working up in gently to the fear that upsets them most (patting a real dog). The more you can help them to feel empowered and in control of their world, the braver they will feel. (For a more detailed step by step description of how to do this, see here.)

• Don’t give excessive reassurance.

If your child has had a genuine fright or is a little broken-hearted, there is nothing like a cuddle and reassurance to steady the ground beneath them. When that reassurance is excessive though, it can confirm that there is something to be worried about. It can also take away their opportunity to grow their own confidence and ability to self-soothe. Finding the scaffold between an anxious thought and a brave response is something every child is capable of. Understandably, it can be wildly difficult to hold off on reassurance, particularly when all you want to do is scoop them up and protect them from the world that they are feeling the hard edges of. What is healthier, is setting them on a course that will empower them to find within themselves the strength and resources to manage their own fear or anxiety. Reassure them, then remind them that they know the answer, or lovingly direct them to find their own answers or evidence to back up their concerns. Let them know you love the way they are starting to think about these things for themselves.

• Understand the physical signs of fear.

Fear might show itself in physical ways. Children might have shaky hands, they might suck their thumbs or their fingers and they might develop nervous little tics. When this happens, respond to the feelings behind the physical symptoms – fear, insecurity, uncertainty.

• Something soft and familiar makes the world feel lovelier. It just does.

Toys or special things might be a familiar passenger wherever your child goes. Let this happen. Your child will let go of the toy or whatever special thing they have when they are ready. Security blankets will often be the bridge between the unknown and familiar, and will form a strong foundation upon which they will build confidence and trust in their own capacity to cope with new and unfamiliar things.

• Be alive to what they are watching on TV or reading in books.

If you can, watch their shows with them to understand how they are making sense of what they see. Some kids will handle anything they see, and others will turn it into a brilliant but terrifying nightmare or vivid thoughts that become a little too pushy.

• Remember they’re watching.

They’ll be watching everything you do. If they see you terrified of dogs, it will easy for them to learn this same response. Remember though, if you can influence their fears, you can influence their courage. Let them see you being brave whenever you can.

• Validate their fears and let them put word to their fears.

Let them talk about their fears. The more they can do this, the more they will be able to make sense of the big feelings that don’t make any sense to them at all. Talking about feelings connects the literal left side of the brain to the emotional right side of the brain. When there is a strong connection between the right brain and the left brain, children will start to make sense of their experience, rather than being barrelled by big feelings that make no sense to them at all.

• Acknowledge any brave behavior.

Because they’ll always love being your hero and it will teach them that they can be their own.

And finally …

It can always be unsettling when fears come home and throw themselves in your child’s way. Often though, fears are a sign that your child is travelling along just as he or she should be. The world can be a confusing place – even for adults. Of course, sometimes fear will lead to a healthy avoidance – snakes, spiders, crossing a busy road. Sometimes though, fear will be a burly imposter that pretends to be scarier than it is.

Fears are proof that your child is learning more about the world, sharpening their minds, expanding their sense of the world and what it means to them, and learning about their own capacity to cope. As they experience more of the world, they will come to figure out for themselves that the things that seem scary aren’t so scary after all, and that with time, understanding, and some brave behavior, they can step bravely through or around anything that might unsteady them along the way.